installation

146600161077

Art is Dead

132174542722

Installation Art by Rirkrit Tiravanija

129950545947

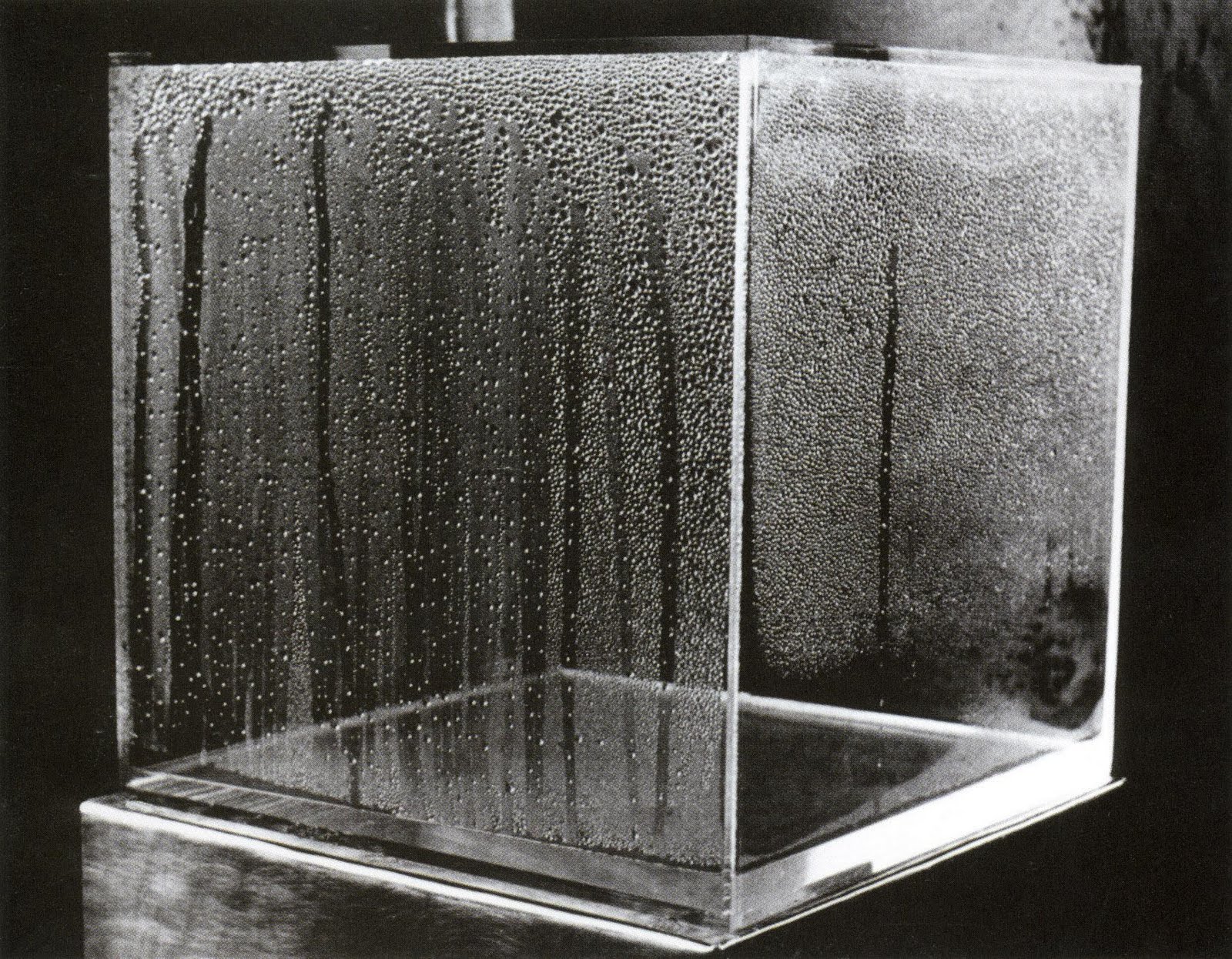

Hans Haacke, Condensation Cube, 1963-65

Installation“I have partially filled Plexiglas containers of a simple stereometric form with water and have sealed them. The intrusion of light warms the inside of the boxes. Since the inside temperature is always higher that the surrounding temperature, the water enclosed condenses: a delicate veil of drops begins to develop on the inside walls.

At first they are so small that one can distinguish single drops from only a very close distance. The drops grow, hour by hour, small ones combine with larger ones. The speed of growth depends on the intensity and the angle of the intruding light. After a day, a dense cover of clearly defined drops has developed and they all reflect light. With continuing condensation, some drops reach such a size that their weight overcomes the forces of adhesion and they run down along the walls, leaving the trace. This trace starts to grow together again. Weeks after, manifold traces, running side by side, have developed. According to their respective age, they have drops of varying sizes. The process of condensation does not end.

The box has a constantly but slowly changing appearance that never repeats itself. The conditions are comparable to a living organism that reacts in a flexible manner to its surroundings. The image of condensation cannot be precisely predicted. It is changing freely, bound only by statistical limits. I like this freedom.”HANS HAACKE, 1965

127574309049

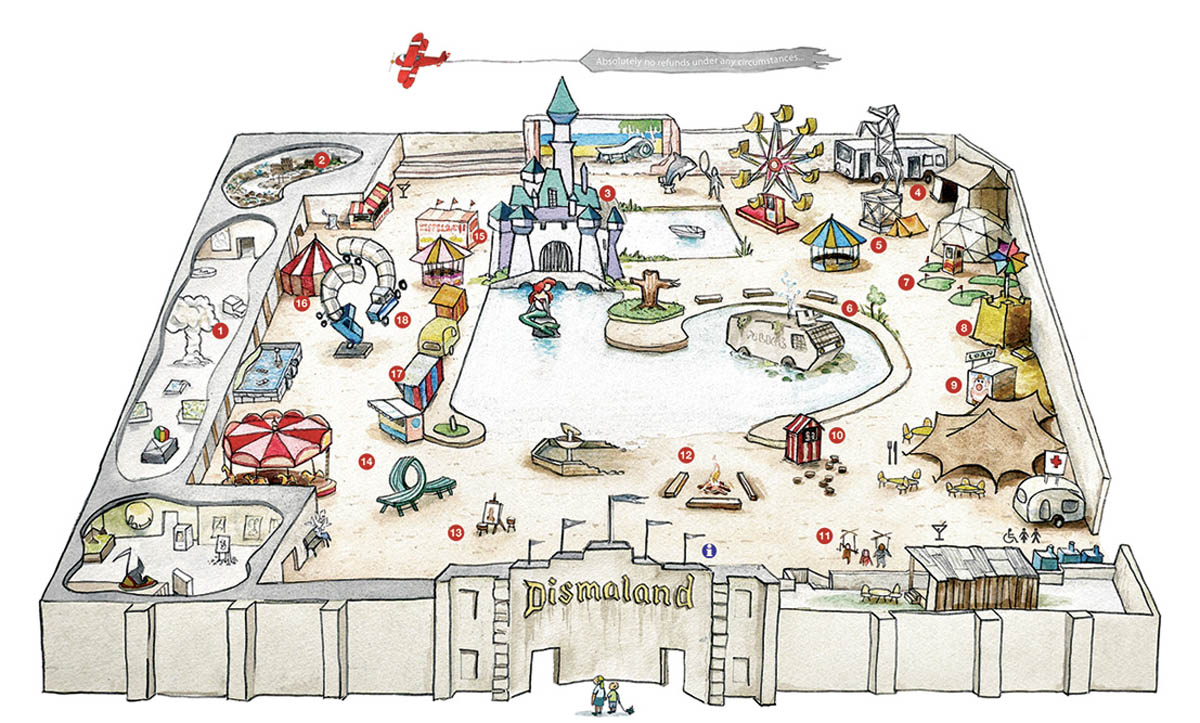

http://dismaland.co.uk by Banksy

126080508397

“It’s as if the artist is the animal and the painting is the record

of the artist’s tracks through space and time … I did not want just a

record, but rather the actual movement.”

‘A Thousand Years’ and ‘A Hundred Years’ were first exhibited at the warehouse show ‘Gambler’, in 1990. ‘A Thousand Years’ is acknowledged by the artist to be one of the most important of his career.

In both works, the vitrine is split in half by a glass wall: a hole

in this partition allows newly hatched flies from a box reminiscent of a

die in one half, to fly into the other where an Insect-O-Cutor hangs.

The corpses of the flies inside the vitrine accumulate whilst the works

are on exhibition. In ‘A Thousand Years’, a decaying cow’s head is

presented beneath the fly-killer.

Hirst describes how, having come round to the idea of the validity of “new art” and having made the spot paintings and the ‘Medicine Cabinets’,

he felt he had lost something, “in terms of the belief I had in whether

[art] was real or not.” Feeling the need to make “something about something

important”, and having already worked with flies, maggots and

butterflies, whilst at Goldsmiths, he decided to create a “life cycle in

a box.” The structure was partially inspired by American minimalism and the

industrial materials Hirst had seen in the work of Grenville Davey and

Tony Cragg. The shape of the vitrine drew from Francis Bacon’s technique

of framing his figures within box shapes. Of the influence of Bacon’s

frames to his work, Hirst has explained: “it’s a doorway, it’s a window;

it’s two-dimensional, it’s three-dimensional; he’s thinking about the

glass reflecting.”

Having planned the works for almost two years, Hirst had to borrow

money from friends in order to finance their fabrication. Despite this,

he insisted on making two, “like bookends”.

Throughout his career, pairs and duplicates have remained an important

element to Hirst’s work. He states: “It undermines this idea of being

unique. There’s a comfort I get from it that I love. Each part of a pair

has its own life, independent of the other, but they live together.”

‘A Thousand Years’ and ‘A Hundred Years’ synthesize two forces

central to Hirst’s work: the desire to create an aesthetically

successful visual display, and an exploration into the deep profundities

of life and death. Although admitting to having a “Frankenstein moment”

of horror at the death of the flies, the use of living creatures

enabled Hirst to incorporate an element of movement into the

works. After studying Naum Gabo, Hirst found that the flies successfully

satisfied his ambition to “suspend things without strings or wires and have them constantly change pattern in space”.

The artist Lucian Freud stated that, with ‘A Thousand Years’ being

one of his earliest exhibited pieces, Hirst had perhaps “started with

the final act”. Explaining that, “your whole life could be like

points in space, like nearly nothing,” Hirst provokes a reconsideration

of how we respond to death in the works; the fate of the flies at the

hands of a machine that is commonplace even in vegetarian restaurants,

is rendered uncomfortable by the gallery setting. Of the thematic prevalence of death in his work, Hirst explains: “You

can frighten people with death or an idea of their own mortality, or it

can actually give them vigour.”

by Damien Hirst