portrait

805177647469608960

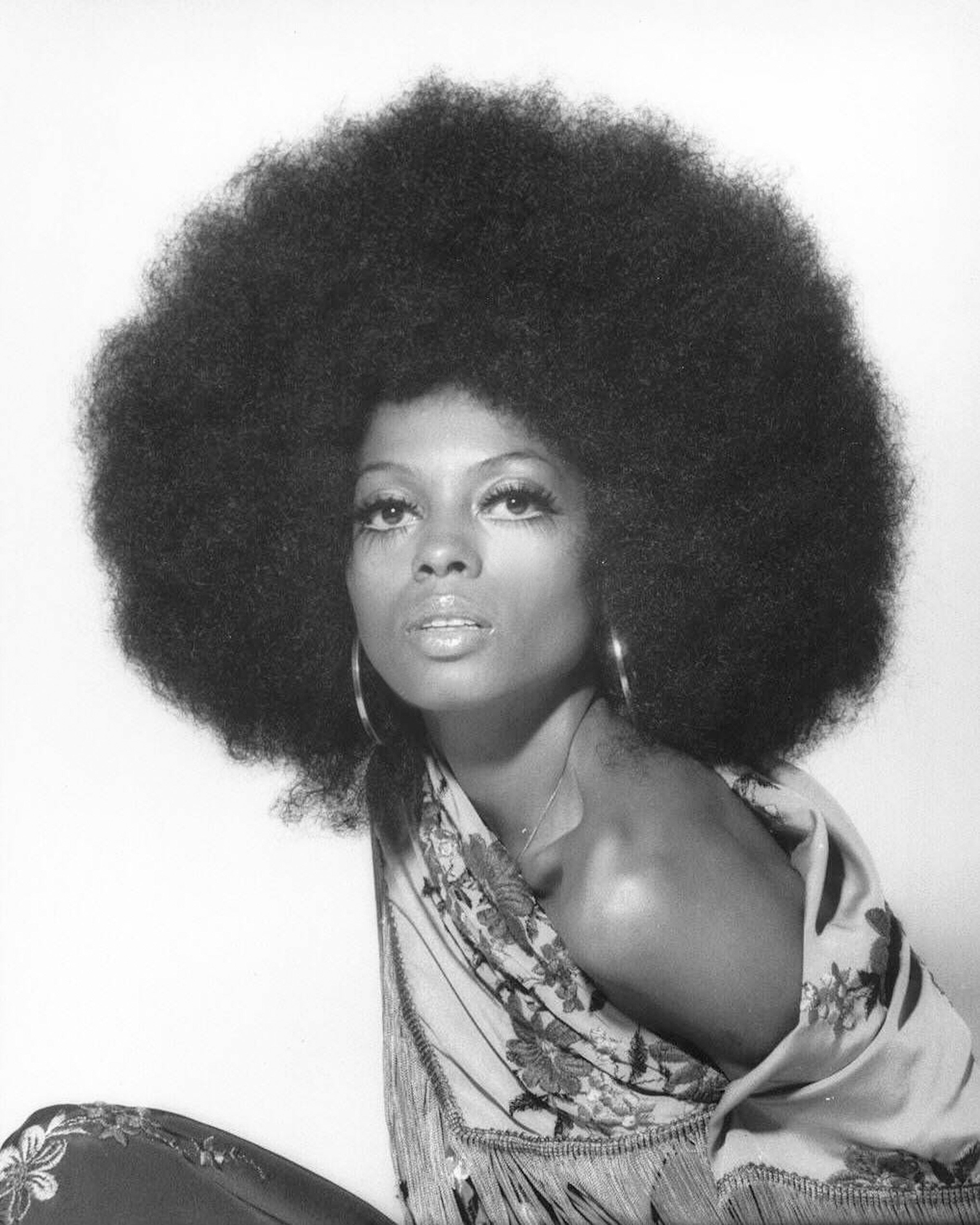

Diana Ross 1975

805156154562985984

Copyright for Artists

Artists need copyright law because it gives their creative work a basic layer of protection, dignity, and sustainability.

First, it recognizes authorship. Copyright law legally links a work to its creator. This matters because art is not just an object, it is an extension of thought, experience, and time. Without that recognition, anyone could claim or reuse the work as if it had no origin.

Second, it prevents unauthorized copying and exploitation. Copyright gives artists control over how their work is reproduced, sold, modified, or distributed. Without it, others could profit from an artist’s labor while the artist receives nothing in return.

Third, it allows artists to earn a living. Many artists rely on licensing, commissions, prints, publishing, or royalties. Copyright makes these systems possible by defining who has the right to monetize a work and under what terms.

Fourth, it protects creative integrity. Artists can object to distortions, misuse, or contexts that misrepresent their work or intent. This is especially important when art carries personal, cultural, or political meaning.

Fifth, it encourages continued creation. When artists know their work will not be freely taken or erased, they are more likely to keep creating and sharing. A system with no protection often favors those with money and platforms, not creators.

At a global level, frameworks like the Berne Convention ensure that artists’ rights are respected across borders, while tools such as Creative Commons allow artists to intentionally share their work on their own terms.

In short, copyright law is not about limiting creativity. It exists to make sure creativity can survive without being taken advantage of.

by ChatGPT

805152121481789440

“If you can’t talk about your art, maybe you don’t know why you’re doing it.”

— Damien Hirst

805151725038256128

Creative Idea Origins

I think creative ideas come from personal experience and curiosity.

From what we live through, what stays with us, and the questions we can’t stop asking. Curiosity pushes us to explore, and experience gives those explorations meaning. When the two meet, ideas start to form naturally, without being forced.

Personal experience gives ideas their weight, and curiosity gives them movement. Experience shapes how you see the world, while curiosity keeps you looking beyond what you already know. One grounds the idea, the other keeps it alive.

When curiosity meets lived experience, ideas don’t feel borrowed or artificial. They feel honest, because they come from paying attention to your own life and still wanting to understand more.

804983979411472384

NFTs and Digital Art

NFTs and digital art remain an important breakthrough not because of short term market prices, but because they solved long standing structural problems that digital creators faced for decades.

For most of its history, digital art was culturally visible but economically fragile. Files could be copied endlessly, attribution was easy to remove, and ownership was impossible to prove in a native digital way. As a result, digital art was often treated as disposable, promotional, or secondary to physical work. Value existed in attention, not in the object itself.

NFTs introduced a technical shift rather than a stylistic one. For the first time, a digital artwork could have verifiable authorship, provenance, and scarcity without relying on institutions, galleries, or centralized platforms. This did not suddenly make all digital art valuable, but it changed the rules of what was possible. Digital works could now exist as collectable objects rather than just images circulating online.

The decline in market prices does not undo this breakthrough. Markets fluctuate, especially early ones driven by speculation. What mattered was not the inflated valuations, but the establishment of infrastructure. Wallets, on chain provenance, creator royalties, and peer to peer ownership created a foundation that did not exist before. Even in a quieter market, these systems continue to function.

Another key shift is psychological rather than financial. NFTs forced a broader cultural acknowledgment that digital labor is real labor, and that digital objects can carry meaning, history, and personal attachment. This parallels earlier moments in art history when new mediums were dismissed before being normalized, such as photography, video art, or digital music files.

Importantly, NFTs also separated validation from traditional gatekeepers. Artists no longer needed approval from galleries or publishers to issue work, document its origin, and reach collectors directly. Even if many projects failed, the principle remains powerful. The ability for creators to define context, edition size, and relationship with audiences is a lasting change.

In this sense, declining prices may even be healthy. They remove speculative noise and return focus to intention, experimentation, and long term practice. When value is no longer guaranteed by hype, the medium becomes more honest and closer to art rather than finance.

Digital art was devalued in the past because it lacked a native system of recognition and ownership. NFTs did not magically solve taste or quality, but they solved that missing layer. Regardless of market cycles, that structural shift remains, and it continues to influence how digital creativity is produced, shared, and understood.

By ChatGPT

804917947850227713

If you ask me, saying art doesn’t need to be explained feels kind of like an old-time way of looking at things.

804917847406018560

Let Art Speak

The use of art descriptions and explanations—especially written ones—has a deep history, but the formal practice developed over time in stages, especially as art moved into public institutions and became part of intellectual discourse.

1. Early Religious and Royal Patronage (before the 1500s):

- No written descriptions were common, but symbolic meaning was built into the artwork itself—especially in religious art.

- In churches, priests or scholars explained artwork to the public orally, especially since most people were illiterate.

- In royal courts, court artists or patrons might include inscriptions or heraldic symbols to convey identity or meaning.

2. Renaissance (1400s–1600s):

- Artists began signing their work and sometimes included Latin inscriptions or visual clues to indicate meaning.

- Thinkers like Vasari (in Lives of the Artists, 1550) began writing biographies and interpretations of artists’ works—this was an early form of art writing and interpretation.

- Patrons also began commissioning works with specific meanings or allegories, often recorded in letters or contracts.

3. Baroque & Enlightenment (1600s–1700s):

- Art academies emerged (like the French Académie des Beaux-Arts), and with them came formal rules and rationales for what art should do.

- Exhibition catalogues started to appear, offering short descriptions of artworks shown in salons or royal collections.

- Paintings were often described in terms of themes, moral lessons, or classical references.

4. Romanticism & Realism (1800s):

- As artists sought to express personal emotion or social truth, art critics like Baudelaire began to write about art in newspapers and books.

- Artists started writing manifestos or letters explaining their intentions (e.g., Courbet’s political realism).

- Public museums like the Louvre or British Museum began offering labels and guided tours—bringing written description to mass audiences.

5. Modernism (1900s):

- As art became more abstract, the need for explanation grew—leading to manifestos (e.g., Futurism, Dada, Surrealism).

- Art critics and theorists like Greenberg, Benjamin, and Berger began interpreting and contextualizing work for readers.

- Museums introduced more sophisticated wall texts, catalogues, and artist statements.

6. Contemporary Art (1970s–present):

- Art description has become nearly standardized—most galleries and museums now include:

- Artist statements

- Curatorial essays

- Wall labels with conceptual and historical context

- Conceptual and installation art especially requires explanation, as the idea is often not visible in the object.

So, while symbolic and oral explanation existed in ancient and medieval times, formal art descriptions as we know them today really took off during the Renaissance, then institutionalized in the Enlightenment, and became essential in Modern and Contemporary art.

by ChatGPT