figure

784883951915483136

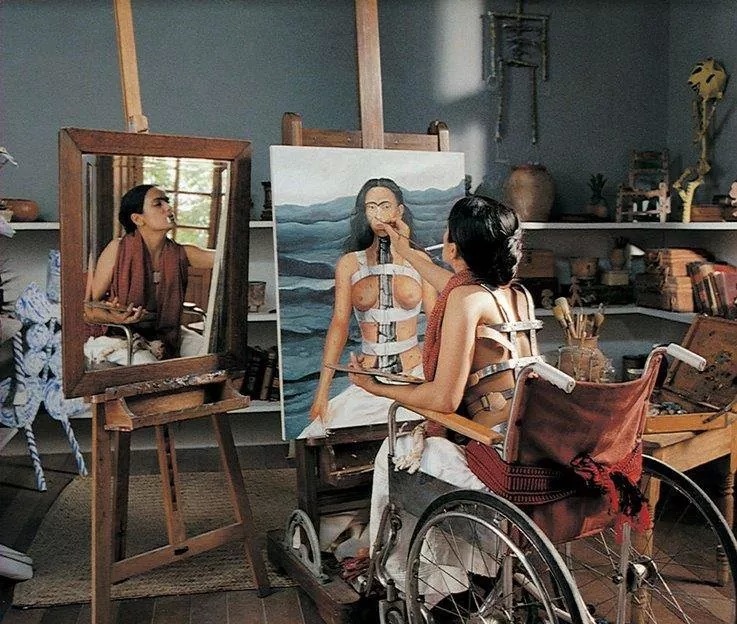

Frida Kahlo (1907.07.06-1954.07.13)

783811569088905216

Guerrilla Girls

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met. Museum

1989

poster

783704490743365632

$70 million Giacometti fails to sell at Sotheby’s modern evening sale.

“Sotheby’s modern evening sale fetched $186.4 million on May 13th. The sale’s most highly anticipated lot—Alberto Giacometti’s Grande tête mince (1955), estimated in excess of $70 million—failed to attract a buyer.”

783434460759801856

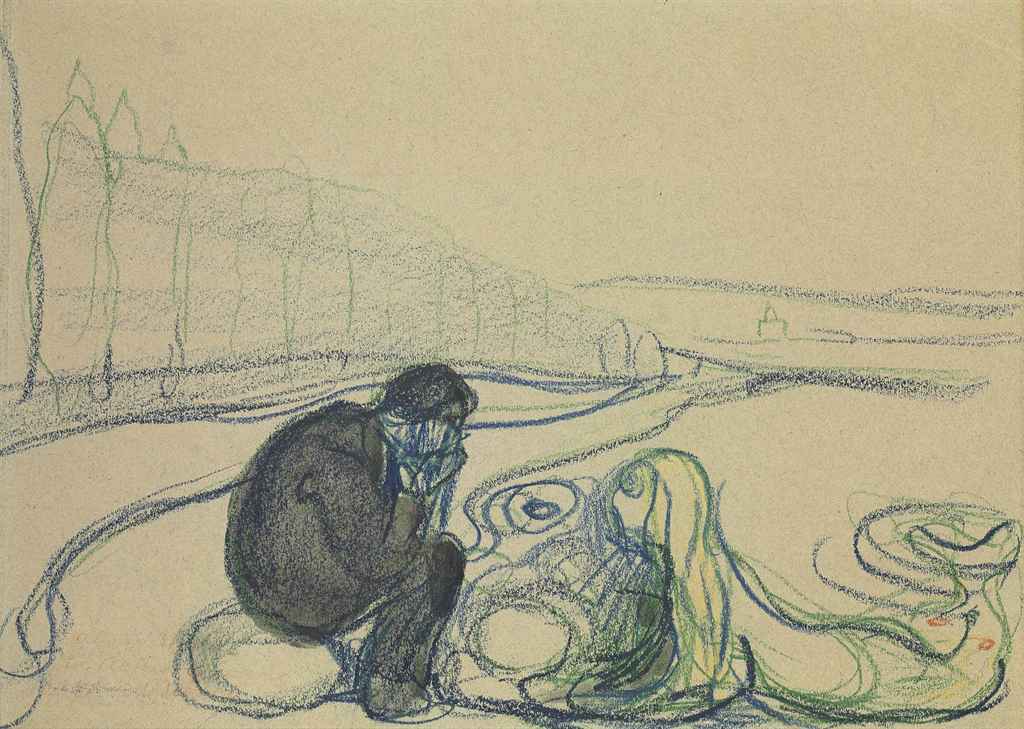

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1945), Melancholy Man and Mermaid (Encounter on the Beach), c.1896-1902. Pastel and wash on paper, 25.3 x 34 cm.

782494155075174400

Van Gogh sold one painting in his lifetime. Was he not an artist?

782442125684047872

Let Art Speak

The use of art descriptions and explanations—especially written ones—has a deep history, but the formal practice developed over time in stages, especially as art moved into public institutions and became part of intellectual discourse.

1. Early Religious and Royal Patronage (before the 1500s):

- No written descriptions were common, but symbolic meaning was built into the artwork itself—especially in religious art.

- In churches, priests or scholars explained artwork to the public orally, especially since most people were illiterate.

- In royal courts, court artists or patrons might include inscriptions or heraldic symbols to convey identity or meaning.

2. Renaissance (1400s–1600s):

- Artists began signing their work and sometimes included Latin inscriptions or visual clues to indicate meaning.

- Thinkers like Vasari (in Lives of the Artists, 1550) began writing biographies and interpretations of artists’ works—this was an early form of art writing and interpretation.

- Patrons also began commissioning works with specific meanings or allegories, often recorded in letters or contracts.

3. Baroque & Enlightenment (1600s–1700s):

- Art academies emerged (like the French Académie des Beaux-Arts), and with them came formal rules and rationales for what art should do.

- Exhibition catalogues started to appear, offering short descriptions of artworks shown in salons or royal collections.

- Paintings were often described in terms of themes, moral lessons, or classical references.

4. Romanticism & Realism (1800s):

- As artists sought to express personal emotion or social truth, art critics like Baudelaire began to write about art in newspapers and books.

- Artists started writing manifestos or letters explaining their intentions (e.g., Courbet’s political realism).

- Public museums like the Louvre or British Museum began offering labels and guided tours—bringing written description to mass audiences.

5. Modernism (1900s):

- As art became more abstract, the need for explanation grew—leading to manifestos (e.g., Futurism, Dada, Surrealism).

- Art critics and theorists like Greenberg, Benjamin, and Berger began interpreting and contextualizing work for readers.

- Museums introduced more sophisticated wall texts, catalogues, and artist statements.

6. Contemporary Art (1970s–present):

- Art description has become nearly standardized—most galleries and museums now include:

- Artist statements

- Curatorial essays

- Wall labels with conceptual and historical context

- Conceptual and installation art especially requires explanation, as the idea is often not visible in the object.

So, while symbolic and oral explanation existed in ancient and medieval times, formal art descriptions as we know them today really took off during the Renaissance, then institutionalized in the Enlightenment, and became essential in Modern and Contemporary art.

by ChatGPT

782285703601160192

“René Magritte’s painting The Rape (1934) is a disturbing and provocative surrealist work. It depicts a woman’s face replaced by the elements of her naked body—breasts where her eyes should be, a navel as a nose, and a vulva in place of the mouth. The image is intentionally jarring and unsettling.

Interpretation: Magritte is often exploring the relationship between images, meaning, and perception. In The Rape, many art critics see a commentary on how women are objectified—reduced to their sexual parts, even in how they’re visually “read” or perceived. By literally substituting a woman’s facial features with sexualized body parts, Magritte confronts viewers with the violence of that objectification. The title “The Rape” reinforces the idea of violation—not necessarily a literal act, but a psychological or visual one.

It’s meant to provoke discomfort and reflection, especially on how women’s identities can be erased or overridden by the gaze of others.”

René Magritte

The Rape

1966

graphite on wove paper

14 1/8 x 10 5/8 in.